Introduction1

Why is solidarity so appealing in times of crisis: Is it the reference to mutual support between social groups and the affirmative use of an imagined ‘we’ which is endangered? Or is it the shared struggle of the weak and most vulnerable groups for a fairer and more equal society and the recognition of power imbalances and unjust social relations that gets more attention in hard times? All these aspects – reciprocal help, social cohesion, fight against inequalities and injustices, questioning modes of domination – relate to solidarity and various scholars focus on these and refer to historical and present examples (Bayertz, 1999; Featherstone, 2012; Scholz, 2008). Times of crisis offer a unique opportunity to learn from these events how actors behaved, what beliefs and ideas prevailed as well as what went wrong for educational purposes. Furthermore, looking at solidarity allows a relational perspective on events, actions and actors that offer new understandings on social and political issues.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented crisis that has had a strong impact on societies across the globe. Hence, the call for solidarity also resonated in this crisis and, as widely reported, countries in Europe are affected by it to different extents. This crisis, however, does not only impact national populations and economies, but also endangers the stability and prosperity of the whole European integration project.

While it is uncontested that the COVID-19 pandemic is a severe crisis, it is less clear how solidarity is linked and enacted in times of crisis. In general, it can be stated that showing solidarity is a matter of mobilization. People demonstrate and show their posters and banners. Protest camps must be established in order to occupy a place and make visible what previously was unnoticed or hidden. The same applies to actions that support others by collecting and distributing money or goods. Moreover, public declarations to act in solidarity also aim to mobilize people, but at the same time, legitimize current actions, because they were grounded in solidarity (Koos, 2019; Wallaschek et al., 2020). No demonstration, protest camp, recurring help or public debates on solidarity last forever. Hence, it is crucial to understand how patterns of discursive solidarity mobilizations relate to actions of solidarity in times of crisis. Hence, my central questions are who shows solidarity with whom and what is the relationship between discursive and actional solidarity during the pandemic?

I try to answer these questions by looking empirically at the COVID19-pandemic in the European Union (EU) and how solidarity is shown in the EU and among its member states between March and September 2020. Based on data provided by the think tank European Council for Foreign Relations (ECFR), I reconstruct the solidarity relations between the EU member states in the first phase of the pandemic.

I will proceed in the following steps: I briefly embed the text in the growing body of solidarity research before I describe the data and present results from the empirical analysis. Afterwards, I reflect on the consequences of the results for educational purposes and discuss further implications of the analysis.

Research on solidarity has not only quantitatively increased, but also produced a variety of solidarity conceptualizations. Based on the recent suggestion by Wallaschek (2020a), we can distinguish between structure-oriented, agency-oriented and discourse-oriented solidarity research. The first one refers to institutions, structures and mechanism that ‘produce’ solidarity. The second approach locates solidarity in certain actions, behaviour and attitudes by individuals and social groups. The third and final approach suggests looking at communicative manifestations and discursive constructions of solidarity (see also Wallaschek, 2020b).

Previous studies have used one of the aforementioned approaches to examine solidarity in times of crisis but rarely brought these approaches together (Baute et al., 2019; Lahusen, 2020; Thijssen & Verheyen, 2020). In an explorative fashion, the present study uses the data from the ECFR to compare the documented actions of solidarity with the publicly declared solidarity claims and thereby brings together the agency-oriented and discourse-oriented approach to solidarity. By doing so, I investigate on the one hand whether the same countries who claim solidarity with others also take related solidarity actions and on the other hand analyse the solidarity relationship between the givers and receivers of solidarity. Hence, to what extent do we observe reciprocal behaviour between countries who show solidarity and countries receiving solidarity (discursively or actional)? And can regional differences be detected that reveal that EU member states in the same territorial region support each other while showing less solidarity to other EU member states?

The European Solidarity Tracker

The ECFR collected data between March and September 2020 on solidarity actions in the EU (Busse et al., 2020). By looking at multiple media sources, official government press releases and other communication channels, they noted who acted with whom in solidarity. The team of the ECFR differentiated between two main types of solidarity: solidarity declarations and solidarity actions. The first one fits into the discursive construction of solidarity approach by referring to public claims that political actors made to show solidarity with others. The second type refers to various actions such as economic support, medical aid or transnational support schemes organized by local initiatives or social groups for others in need. These forms of solidarity fit into the agency-oriented solidarity approach. The ECFR team also noted who declared solidarity with whom, what kind of solidarity is mentioned on which date and collected the data for all EU member states. Based on this comprehensive data set, I apply a social network analysis that treats countries (the EU as polity and the EU27) as nodes in the network and the types of solidarity as edges between nodes. In total, the network includes 29 nodes and 283 edges. The data set also contains the two types of solidarity (discursive and actional solidarity), notes who is the sender and who is the receiver of solidarity, and based on the EuroVoc (n.d.) classification, EU member states are sorted into four different European regions (Northern, Central and Eastern, Southern, Western). References to the EU in general as well as to the EU if the actions or claims refer to the EU27 are also noted. Furthermore, solidarity is conceptualized as a directed relation, because one actor gives solidarity and the other receives solidarity. These two directions are analysed in terms of in- and out-degree centrality (Hanneman & Riddle, 2011). In-degree centrality means the number of ties a node receives from another node (namely receiving solidarity) whilst out-degree centrality means the number of ties a node sends to another node (namely showing solidarity). By doing so, it is possible to look specifically who shows solidarity with whom during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the EU.

Results

In the following, I proceed in two steps. First, I present an overview of solidarity relations by comparing the networks in terms of in-degree and out-degree centrality. Second, I differentiate between the two types of solidarity and show them in two separate networks. Hence, we can compare who shows solidarity with whom and what kind of solidarity is demonstrated. This provides a nuanced understanding of the actors of solidarity and how different types of solidarity converge or diverge during the COVID-19 pandemic.

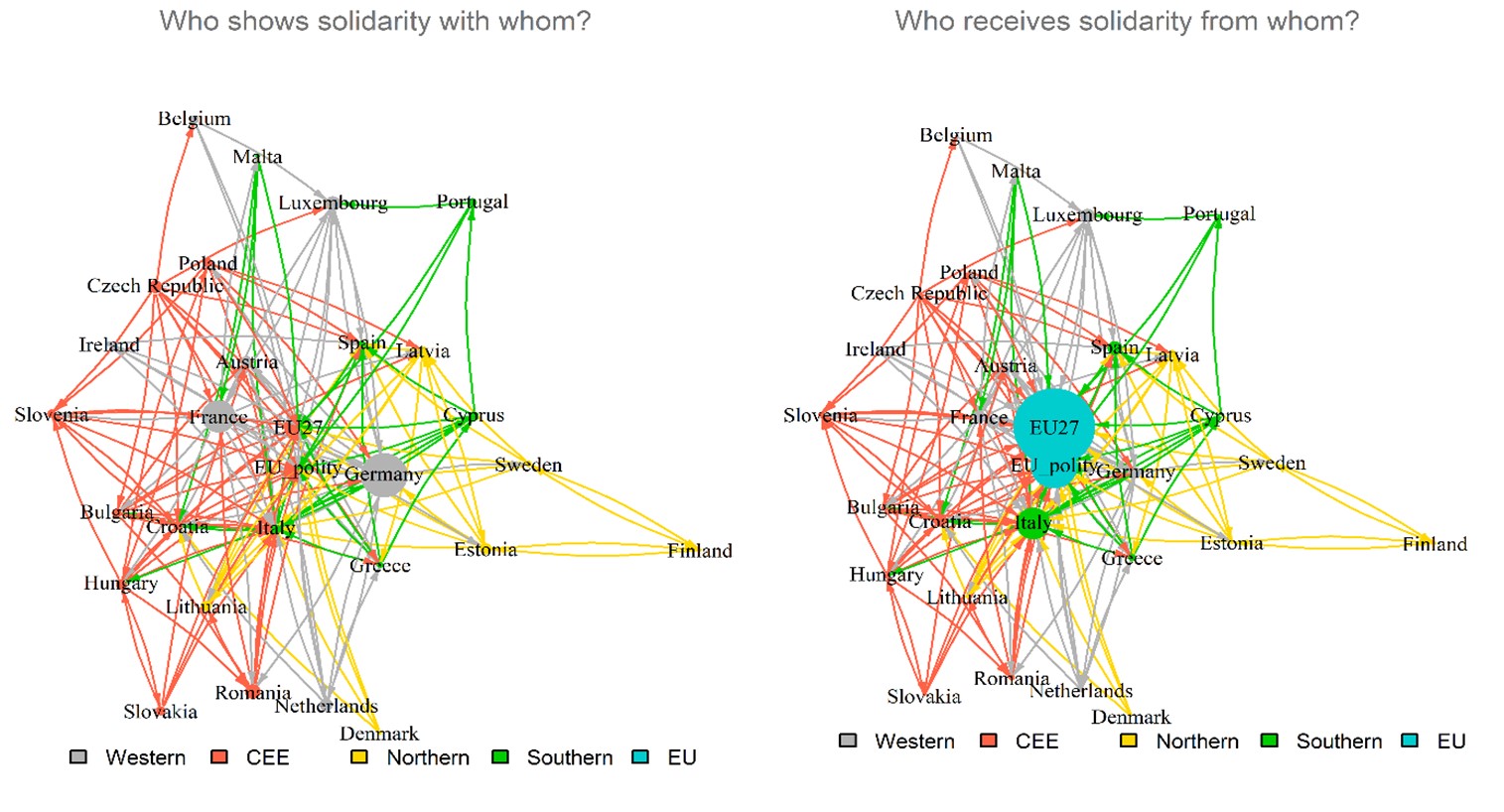

Figure 1 focuses on the relationship of giving and receiving solidarity during the first phase of the pandemic. On the left, we see that Germany and France show solidarity with a variety of different countries.2 For instance, Germany provides masks and other medical supply to Italy and Austria in March while the French government repeatedly declares solidarity with Italy. Both countries also show solidarity with other EU member states such as Romania and Croatia (i.e. providing masks and medical equipment) as well as supporting EU-wide actions such as the establishment of the EU recovery fund. Otherwise, the graph shows that Northern countries (Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia) as well as Central and Eastern European countries (Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia) give solidarity to other countries in their respective regions. While France and Germany are clearly politically the most influential member states and the economic powerhouses in the EU, the regional solidarity relations point towards a certain degree of geographical proximity towards neighbouring countries (which is also to some extent reflected in the various links between France and Germany). Whilst the EU is not a central actor in showing solidarity – obviously – the level of the EU27 as well as the EU in general receives a lot of solidarity attention. The majority of the member states show solidarity on the European level in one way or another by giving money to EU-wide funding schemes, contributing to economic recovery packages, participating in European vaccination coordination strategies and publicly declaring solidarity with other member states or the EU. Hence, the EU is a crucial receiver of solidarity from its member states. Subsequently, Italy and Spain as the countries who were hit the hardest by the COVID-19 virus also received many offers of solidary from multiple sites, followed by Luxembourg, Croatia and France. In contrast, Belgium, although having a high share of COVID-19 cases among the population received less attention from member states.3 Accordingly, we identify a parallel attention to solidary with respect to the European level as well as support for neighbouring countries.

Figure 1: Solidarity network among EU member states (in-degree and out-degree centrality)

Source: ECFR; Note: own illustration; The node size in the left network graph is based on out-degree centrality, the node size in the right network graph is based on in-degree centrality. The edge colours are based on the outgoing direction, namely who shows solidarity with whom. |

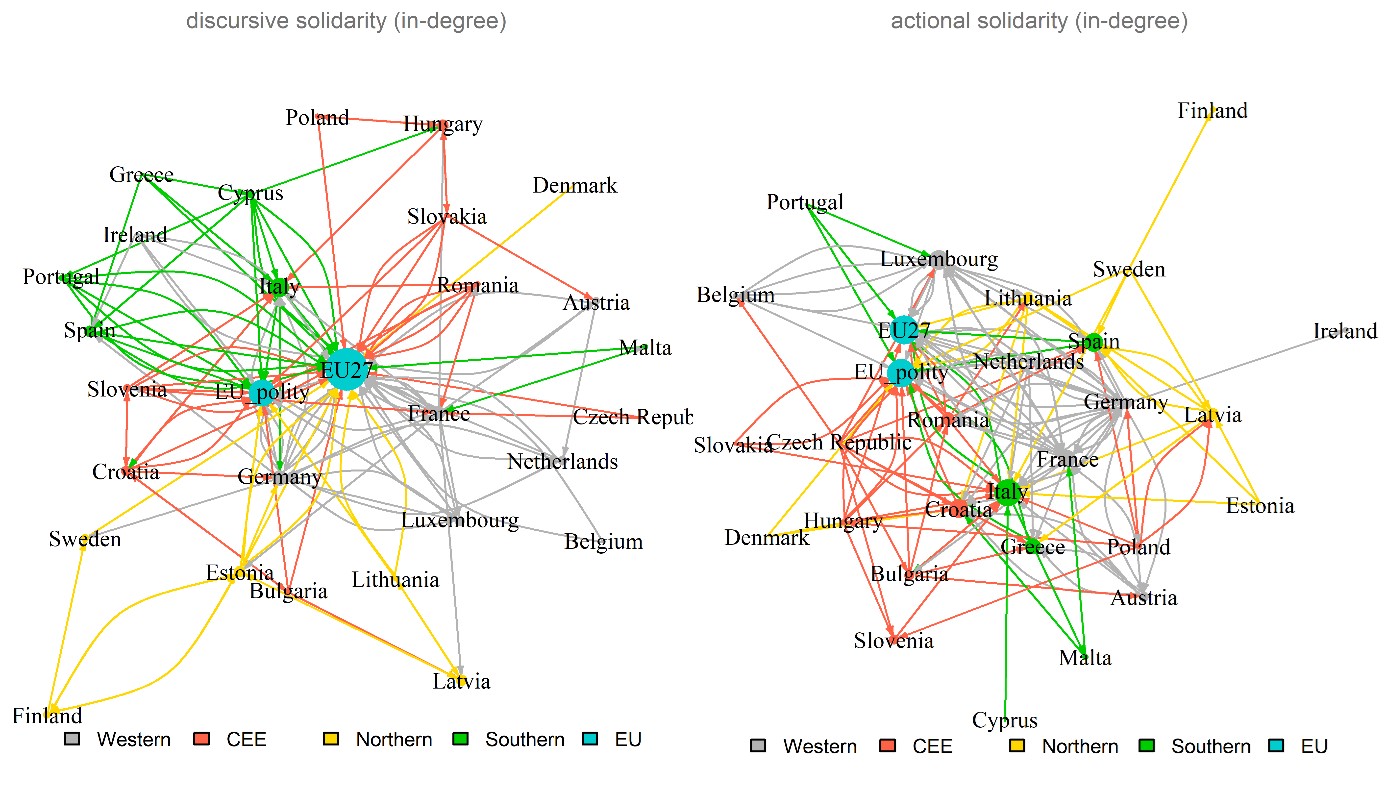

In the second step, we turn to the two types of solidarity – discursive and actional solidarity. Whilst the former networks did not separate them, Figure 2 shows two networks: the left network displays the public solidarity claims, and the right network shows the action solidarity relations during the first phase of the pandemic (March to September 2020). I want to highlight two crucial findings. First, the EU – as a group of member states (EU27) as well as a polity community (EU_polity) is the main addressee of solidarity discursively as well as in actional terms. Despite the different solidarity types, this is a shared characteristic in both networks. It underlines that public claims and actions towards solidarity do not strongly differ although the discursive solidarity towards the EU was used more (in total) than actions towards the EU.4 Second, the regional solidarity patterns differ between the two networks. With regard to discursive solidarity, a Southern (Cyprus, Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy) and a Northern (Finland, Estonia, Sweden, Latvia) cluster can be identified, the actional solidarity cluster is only similar for the Northern countries (Finland, Sweden, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania); interestingly Denmark is not connected to other Northern European countries in both networks. The actional solidarity network shows a strong dispersion. For instance, Poland supports Slovenia and Hungary, but also Latvia and Italy in the pandemic.

Figure 2: Discursive and actional solidarity network among EU member states (in-degree centrality)

Source: ECFR; Note: own illustration; The node size in the two network graphs is based on in-degree centrality. The edge colours are based on the outgoing direction, namely who shows solidarity with whom. |

Lessons for teaching solidarity to students

Which educational lessons can be drawn from the analysis of solidarity during the COVID-19 pandemic? First, studying times of crisis offers the opportunity to look at potential rapid change or surprising stability in turbulent times. Crises could be understood as moments in which actors re-think their mindset, act in surprising ways (or not) and modes of cooperation and conflict are created that might be quite different from the ‘business as usual’-mode (Hay, 2006, p. 67). Having times of crisis as guiding ideas in history or politics curricula might help students (and teachers) to communicate and exchange views on how societal change and political transformations come about and impact societies and politics. The daily use of social media by young people might be a specific access point to engage with crises. Social media brings any crisis on to your mobile phone or tablet with a few clicks and ordinary citizens can make a statement, reply to others via hashtags and posts and by doing so they partially re-produce the crisis narrative itself. This could be a good thing, because students can engage with and experience crises more directly than they would by learning from past crises from which they feel more distanced. It could create instances of belonging, relating to others and showing empathy. For instance, looking at Instagram posts or sharing tweets from strangers who have had COVID-19 and share their medical treatment story or retweeting experience reports from doctors who work in hospital with many

COVID-19 cases may start a crucial reflection process for students, demonstrating that crises are not necessarily events of the past. Otherwise, as Chouliaraki (in this issue) points out, sharing, retweeting, or liking social media posts might be less a sustainable solidarity action and might rather be a form of ‘lifestyle solidarity’. Such posts target more public attention and try to convey a certain message or brand on social media than aiming for social change or empathy with others. However, I would argue that reflecting on how students experience crises and solidarity and engage with those on social media platforms should be a crucial pedagogical task in school and higher education institutions.

Second, using solidarity as a lens to study political and social topics might offer a unique cognitive mindset because in order to grasp solidarity, a relational perspective is needed. Solidarity – whether discursive or actional – requires a relationship and at least two actors who behave as counterparts: Actor A shows solidarity with actor B and in a potential time-delayed manner, actor B enacts reciprocity with actor A. It is crucial to understand that actors are embedded in structures and create relations between different actors and social groups by either discursively appealing to solidarity or by undertaking any kind of solidary practice. Acting in solidarity resonates between the actors involved, and shapes their actions and how they respond to future cooperation (see also Fichtner in this issue). In school or higher education learning settings, this could mean that new curricula formats for history or politics classes are developed. Instead of getting to know historical events, international politics and political actors as distinct and separated entities that can be learned independently from each other, a relational understanding would stress the interconnectivity of events and how actors are embedded in webs of relations. These relations become even more relevant in times of crisis because certain relations become more important than others or even get disconnected due to civil conflicts, economic crises or natural catastrophes. Accordingly, for historical and social science issues in education, a relational perspective offers the chance to study times of crisis and solidarity in an interdependent way. By doing so, students can learn which actors mutually supported each other (and which actors did not), under which circumstances, based on which interests and beliefs and thereby, learn history and current topics through the lens of solidarity, namely as modes of cooperation and conflict.

Conclusion

Solidarity resonates quite strongly in times of crisis because it promises to overcome this crisis by actions of mutual support and standing together. The pandemic seemed to be a paradigmatic case to test the existence of European solidarity (Wallaschek & Eigmüller, 2020). This crisis could also be a crucial reference scenario in classes and seminars to learn more about crises, share experiences and debate different types of solidarity among students.

By using data collected from the ECFR, I illustrated solidarity relations that have been created, either by public claims or by concrete actions from one country to another. I demonstrated that the EU was an important receiver of solidarity – in terms of public claims as well as with concrete action schemes. The EU acted as a distributive hub to which member states turned in order to give money, provide medical supplies or technical assistance that could be later distributed to several member states. Moreover, declaring solidarity with the EU was also an important discursive claim in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we see an overlap of discursive and actional solidarity with regard to the EU and to a less extent with regard to solidarity relations among the EU member states. The analysis has also demonstrated that both types of solidarity are shown to member states in the same region, creating for instance discursive as well as actional solidarity relations among Northern European member states. The congruence of both types of solidarity highlights the crucial role that the EU and cooperative actions among EU member states can play to overcome this long-lasting crisis. The widely shared belief that the EU and its member states did not do anything and hardly cared about the other countries can be somewhat contrasted with these findings. 5

Nonetheless, and as the EU summit in July 2020 vividly demonstrated (as well as the previous crises in the EU), showing and declaring solidarity in the short-term is just one side of the coin. The other is the institutionalization of solidarity in order to not only counter the immediate effects of the crisis, but also the long-term outcomes and the societal and economic impact of the pandemic. Lasting solidarity, namely agreeing on structures and mechanisms that countries could rely on in future crises may be the biggest fault line in the EU. While the EU recovery fund might have been a first step towards a more institutionalised solidarity scheme, the limited time frame as well as a tightening of the rules and conditions through the repeated criticism from several member states (such as Austria or Finland) have served to weaken the idea of European solidarity among EU member states in pandemic times. Accordingly, seeing solidarity as being part of the actions and public claims by EU member states in the first phase of the COVID-19-pandemic is just a first and probably the easier step than the second step of establishing a European solidarity structure.6

To conclude this discussion, and in order to matter and resonate in public, the idea of solidarity also rests upon educational institutions which can give attention to solidarity (conflicts) in curricula and convey ideas of solidarity between students and teachers in class (see also Kymlicka in this issue). Such educational opportunities can lay the ground for citizens to support future European solidarity actions and even structures that are missing so far.

References

Baute, S., Abts, K., & Meuleman, B. (2019). Public support for European solidarity: Between Euroscepticism and EU agenda preferences? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 533–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12833

Bayertz, K. (1999). Four uses of “solidarity”. In K. Bayertz (Ed.), Solidarity (pp. 3–28). Springer.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9245-1_1

Busse, C., Franke, U. E., Loss, R., Puglierin, J., Riedel, M., & Zerka, P. (2020, June 11). European solidarity tracker. ECFR. Retrieved January 3, 2021, from https://ecfr.eu/special/solidaritytracker/

EuroVoc. (n.d.). Browse by EuroVoc. Retrieved January 19, 2021, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/browse/eurovoc.html?params=72,7206#arrow_7206

Featherstone, D. (2012). Solidarity: Hidden histories and geographies of internationalism. Zed Books.

Hanneman, R. A., & Riddle, M. (2011). Concepts and measures for basic network analysis. In J. Scott & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social network analysis (pp. 340–369). SAGE.

Hay, C. (2006). Constructive institutionalism. In R. A. W. Rhodes, S. A. Binder, & B. A. Rockman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political institutions (5. ed, pp. 56–74). Oxford University Press.

Koos, S. (2019). Crises and the reconfiguration of solidarities in Europe – origins, scope, variations. European Societies, 21(5), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2019.1616797

Lahusen, C. (Ed.). (2020). Citizens’ solidarity in Europe. Civic engagement and public discourse in times of crises. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789909500

Scholz, S. J. (2008). Political solidarity. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Thijssen, P., & Verheyen, P. (2020). It’s all about solidarity stupid! How solidarity frames structure the party political sphere. British Journal of Political Science, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000137

Wallaschek, S. (2020a). Empirische Solidaritätsforschung: Ein Überblick. Springer VS.

Wallaschek, S. (2020b). The discursive construction of solidarity: Analysing public claims in Europe’s migration crisis. Political Studies, 68(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719831585

Wallaschek, S., & Eigmüller, M. (2020). Never waste a good crisis. Solidarity conflicts in the EU. In M. Donoghue, & M. Kuisma (Eds.), Whither social rights in (post-)Brexit Europe (pp. 60–69). Social Europe Ltd.

Wallaschek, S., Starke, C., & Brüning, C. (2020). Solidarity in the public sphere: A discourse network analysis of German newspapers (2008–2017). Politics and Governance, 8(2), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2609

Zaun, N. (2018). States as gatekeepers in EU asylum politics: Explaining the non-adoption of a refugee quota system. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12663

Recommended Citation

Wallaschek, S. (2021). Who has shown solidarity with whom in the EU during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020? Lessons for teaching solidarity to students. On Education. Journal for Research and Debate, 4(10). https://doi.org/10.17899/on_ed.2021.10.10

Do you want to comment on this article? Please send your reply to editors@oneducation.net. Replies will be processed like invited contributions. This means they will be assessed according to standard criteria of quality, relevance, and civility. Please make sure to follow editorial policies and formatting guidelines.

- I would like to thank Franziska Ziegler, Simona Szakács-Behling and Christian Brüggemann for constructive comments on earlier versions of the text. ↵

- The top four countries with the most solidarity relations to others (out-degree) are Germany, France, Luxembourg and Romania. The countries with the least solidarity relations are Finland, Denmark and Malta. ↵

- The top three countries (besides the EU and EU27 itself) who received the most solidarity actions (in-degree) are Italy, Spain and Luxembourg. The countries who received the least solidarity actions are Czech Republic and Denmark (received no solidary support during this time) as well as Belgium, Portugal, Ireland and Slovakia (received solidary support one time). ↵

- Besides the EU, Italy, Spain and Luxembourg also received many actional solidarity because these countries have been hit hard by the pandemic. Regarding discursive solidarity and apart from the EU, Italy, Germany and France received the most discursive solidary support. ↵

- The data from the ECFR does not include actions or public claims that explicitly refused solidarity actions from either one member state to another or to the EU. However, there have been conflicts about who should get what or claims that a member state did not feel supported by the EU during the pandemic. Moreover, another (normative) question is whether these solidarity actions were enough and successful in combating the pandemic in the EU or whether the member states and the EU should have done more and faster to contain the virus and lower the effects on the population and economy. However, these questions go beyond the scope of this text. ↵

- A similar solidarity debate was going on in Europe’s migration crisis. Many member states initially supported a reform of the European Common Asylum System and declared solidarity with other member states in 2015. The actual instalment and implementation of an EU solidarity mechanism to relocate refugees across the EU and share responsibility was highly contested and failed at the end (Wallaschek, 2020b; Zaun, 2018). ↵