What’s at Stake?

Teachers are both controlling agents and controlled subjects, in any educational system. They manage, develop, and thereby control the classroom in one or the other way; while they are at the same time trained and recruited to implement the curriculum and wider educational policies, of which they have no direct ownership. Educational research has approached this dual role from a variety of practical and theoretical angles, the most notable perhaps being the perspective of teacher autonomy as it is negotiated between, simply speaking, structure and agency (see e.g., the overview in Wermke, 2013). This essay does not deny the importance of the many studies that have contributed to our understanding of teacher autonomy; but it urges to more critically illuminate the relationship between our conceptions of teacher agency on the one side, and student empowerment (or control) on the other. Under what circumstances can increased teacher agency lead to more student empowerment, and generally to a more democratic understanding of schooling? And, can we think of converse relationships, in which strengthened teacher agency may be able to constrain student empowerment? Or, alternatively, in which pedagogical designs aiming at increased teacher agency actually have the reverse effect on teachers’ scopes of action, and lead to neither increased teacher agency nor student empowerment?

Rather than framing this essay as a general argument about teacher agency and student empowerment, I will draw on my own observations from doing fieldwork at Chinese schools over the last ten years. Obviously, the Chinese school context is different from, for example, European or North American contexts in many ways. It is rooted in distinct historical traditions and shaped by a distinct political system – a form of authoritarian leadership that officially adheres to a socialist ideology, but practically follows capitalist principles (as long as they do not jeopardize the one-party rule). Both cultural and political factors have an imprint on how children are schooled and how teachers are trained. However, looking at a fundamentally different context also gives us the chance to see aspects that we tend to overlook too quickly, since they have been naturalized within our own horizons of understanding. Among these naturalized aspects, I argue, is the conflation of teacher agency with student empowerment: the outspoken or tacit assumption that the former will lead to the latter, or at least, that the former does not stand in the way of the latter.

To make my argument more concrete, I will focus on the use of digital technologies, or information and communication technologies, for educational purposes (in the following, ICT4E). ICT4E have been associated with a range of benefits (see next section), among them their conduciveness for more diversified teaching and for more interactive, student-centered learning. These again have been linked to both more student participation and strengthened teacher agency – as opposed to conventional teaching and learning styles that are deemed to force teachers and students into too rigid a frame. I will first present what has been discussed to be the virtues of ICT4E, particularly within unequal and unjust educational contexts. In an ensuing section, I will question the naturalized relationship between teacher agency and student empowerment, to then scrutinize how ICT4E, teacher agency, and student empowerment play out in two related but different contexts: rural China and urban China. I will conclude by arguing that we need not lose sight of our normative and political assumptions when discussing teacher agency.

The Educational Promises of the Digital

Education and schooling are known to be social mobilizers: a sufficient quantity of good-quality schooling has been associated with an increase in cultural, social, and eventually also economic capital, and both national governments and international organizations have linked the performance of school systems to people’s well-being and economic growth. Yet, we are equally aware of continuing inequalities and divides in education: not everyone has access to the same quality of education. Various boundaries prevent children and adults from enjoying good education, among them national and intranational, cultural, ethnic, religious, gender-based, political, and economic boundaries. What’s worse, schools have been found to not only be unequally accessible, but also to reproduce and thereby cement existing divides: if attending high-quality schools is the privilege of a few, their mere existence exacerbates the exclusivist effects of education.

Teachers have been identified as crucial factors for the mission of turning schools into more equitable and better-quality institutions, and for teaching the skills and the knowledge that are deemed relevant for today’s knowledge economy. They are seen as central implementors of an up-to-date curriculum and thereby as important agents of improvement and change, while at the same time they are often blamed for a variety of educational failures (Fontdevila & Verger, 2015). As much as good-quality schools are unevenly distributed across the social-geographic landscape, also teacher resources are marked by an unequal distribution: Low-performing schools, or otherwise disadvantaged schools – such as schools in rural, poor, or violent areas – tend to have more difficulty in attracting well-educated, competent teachers; while privileged schools usually have no trouble in recruiting qualified teaching staff.

One frequently discussed solution to the problem of uneven school and teacher quality has been to utilize ICT4E. Particularly in developing countries, where the above-described inequalities and divides are even more palpable than in wealthier societies, ICT4E are seen as a feasible way to improve education and reach the sustainable development goals as specified by the United Nations (Wagner, 2018).

Regarding inequalities in education, several arguments have been made in favor of using ICT4E (see also the overview in Schulte, 2018a):

- Bridging various divides: since ICT are potentially available irrespective of locality, social class etc., they are deemed the ideal means to bridge the divides that have been shaping schooling and education. Potentially, they enable the student from a poor or remote rural area to access the same knowledge resources as they are available to the rich urban student.

- Compensating for an unequal distribution of teacher resources: ICT are seen as ensuring access to high-quality teaching and learning material as well as innovative pedagogies (e.g. through online lectures), so local schools and students are no longer dependent on a small number of excellent teachers.

- Cost-effectiveness: once infrastructure and hardware are in place, ICT are considered cost-effective means to improve education – in contrast to, for instance, hiring expensive teacher-experts or paying higher salaries (or other benefits) to make disadvantaged areas more attractive for good teachers.

Regarding teachers and school quality in particular, ICT4E are considered to be able to contribute in the following ways:

- Professional training for teachers: further education and training for in-service teachers have long been problematic in educational systems that are marked by stark quality differences across the country; ICT4E are considered viable means to engage teachers in professional, lifelong learning in a standardized and cost-effective way.

- Opportunities for communication and knowledge-sharing among teachers: in addition to formalized pathways, ICT4E are also seen as opening possibilities for teachers to share their knowledge as accumulated in practice, and exchange views on various pedagogical or didactical issues.

- Making teaching and learning more interactive and student-centered: finally, ICT4E are believed to not only serve as vehicles of change, for example, by being more adaptive and cost-effective than human or other material resources; they are also expected to transform teaching and learning by their very nature of being information and communication technologies. This view is due to their potential multi-way communication modes (as opposed to, say, a book that presents a one-way communication mode) as well as their potential responsiveness to teacher and learner characteristics and demands (e.g., shifts in content or learning strategy can be made part of the programming, thus making teaching and learning more interactive).

To be sure, these are the ideal benefits of ICT4E. Both the research literature (e.g., Lankshear & Knobel, 2008) and more strategic documents (e.g., OECD, 2015) have cautioned against a too simplistic understanding of ICT4E, and have identified a range of factors that can hinder the positive effects of ICT4E. Yet, none of these critiques has problematized the basic causal assumption that the correct implementation of ICT4E will lead to increased teacher agency and thereby student agency and empowerment.

Teacher Agency and Student Empowerment: A Simple Relationship?

Are teacher agency and student empowerment two sides of the same coin? Curiously, the relevant literature either ignores the question of how increased teacher agency has an effect on student empowerment, and is instead concerned with questions of professional autonomy, for instance, versus new management forms and accountability regimes; issues of student participation and empowerment are seldom linked to these questions (Wermke, Olason Rick, & Salokangas, 2019). Or it is tacitly assumed that increased teacher agency is accompanied by more student empowerment. In this strand of scholarship (or advocacy literature?), teachers are thought of as positive agents of change, who act for the cause of social justice and equity – which is often opposed to a perceived trend of de-professionalizing teachers (Priestley, Biesta, & Robinson, 2013). The common enemy in this account – to both teacher and student agency – is high-stakes testing and other threats to creative and critical thinking.

Even when teacher agency is conceptualized as being embedded in a complex social context – for example, in what Priestley et al. (2013) call an ecological approach – there is still the implicit assumption that increased teacher agency serves some sort of (morally, ethically) better purpose. Clearly, teacher agency cannot be detached from the researchers’ own underlying normative conceptions; for example, that such an agency will put emphasis on dialogue and collaborative work, on students as co-participants, and generally on what we like to consider the emancipatory traditions in pedagogy (see e.g., Cloonan, Hutchison, & Paatsch, 2019; Samoukovic, 2015). In these approaches, teacher autonomy is often conflated with learner autonomy, assuming that the first will lead to the latter (Benson, 2007).

Ironically – and despite the fact that much of this scholarship could be called political, inasmuch as it calls into question prevalent political (and neoliberal) hegemonies – such an approach to teacher agency is deeply apolitical. It frames teacher agency as a sine qua non to good education irrespective of political conditions: that is, as something indispensable and desirable, regardless of what potential detrimental implications certain kinds of teacher agency may have for student empowerment in certain contexts. Such complicity between teachers and researchers, as we may also conceive of it, can be explained by our own rootedness in rather particular pedagogical traditions – traditions that resonate with core ideas about democracy and empowerment through pedagogy, such as in John Dewey’s (1916) and Paolo Freire’s (2005 [1970]) works. Historically, ideas of a more participatory pedagogy have been intertwined with perspectives on schools and students that stress empowerment and democracy.

Such intertwinement, if taken for granted and naturalized, can be misleading. Firstly, there are many societies around the world who do not share the same history of pedagogy, and where teacher agency may have very different connotations. Secondly, even within Western contexts, there are warnings that the original goals of social justice and equity may get lost in a more instrumentalist perspective on student-centered learning, which links pedagogical technologies to student performance and assessment, rather than to issues of critical democracy (Pinto et al., 2012). It is therefore important to not confuse teacher agency with student empowerment, or, put more cautiously, to automatically assume that strengthened teacher agency will have positive effects on self-directed learning among students. Teachers can have more or less agency, but how this impacts student empowerment – or conversely, how this may lead to more control of students – depends on the larger societal and political context: teachers can be agents for social justice; or for the mission of their individual school, or the wider educational system; or for political and other missions that do not necessarily (completely) overlap with what the school or the educational system regard as their primary missions.

In another article (Schulte, 2018b), I have discussed how teachers are engaged in a continuous ‘politics of use’: when enacting the curriculum (or more broadly, educational policies), teachers unavoidably – and at times inadvertently – put values into use, and they do so with regards to both micropolitics (e.g., school politics) and macropolitics (e.g., larger political ideologies). Under certain circumstances, and as has become evident from my fieldwork in China, the goals as communicated by agents such as the central government may for example override those of the educational system or the individual school – without any formal, institutionalized mechanisms that would officially allow for such side-stepping. Teachers may thus use their agency in spite of their immediate environments (the school, the educational system), and instead turn to larger political narratives. On whose behalf, and for what greater purpose teachers are agents for, is something that needs to be investigated empirically, rather than be assumed a priori.

At first glance, ICT4E have nothing to do with these questions of agency and empowerment. After all, they provide only the material means and should thus be neutral to these questions. However, technologies – particularly interactive, adaptive, and responsive technologies – play a crucial role: they can amplify certain effects on agency as well as on empowerment. They can for example provide more options to teachers, help them build a base of professional knowledge and practice, and support them in making autonomous decisions regarding teaching material and pedagogies (instead of e.g., forcing teachers into following narrow guidelines with little material); but they can also exercise a streamlining effect on teachers, by standardizing teaching content and pedagogy without much room for deviations. In contrast to, say, books, ICT are particularly capable of tracing whether or not teachers follow guidelines or program features faithfully. Similarly, ICT4E can increase interactivity among students and help in granting them more space (both individually and collectively – e.g., through tailored learning sessions or group platforms). But they have also the power to subject students to more thorough influence from authorities that before have had more indirect effects on school practices in the classroom. For example, while school books and much other printed learning material have to go through rather tedious processes of quality control and accreditation, powerful agents such as governments or companies can use ICT4E to quickly access students, for instance, through social media and/or teachers utilizing these media in class.

My empirical questions for the ensuing short section are directed to contexts where there has been heavy investment in ICT4E: rural and urban China. In rural China, teachers’ professional expertise is to be strengthened through ICT4E; the new technologies are expected to transform the rural teacher into a knowledgeable, autonomous professional. In urban China, ICT4E are to improve the teachers’ teaching skills and adapt teachers to the requirements of the twenty-first century, by making teaching (and learning) more student-centered, interactive, and creative.

So, my questions are, firstly: Do ICT4E grant agency to the rural, marginalized teacher? And, secondly: Can the urban, privileged teacher improve her teaching skills, gain agency through ICT4E, and make learning more student-centered, interactive and creative – and hence more democratic and empowering?

The short answers to both questions are: technically and hypothetically, there is indeed the opportunity for both more teacher agency and student empowerment. In practice, however, and due to the particular contexts in which schools and teachers are situated, we can see, in one case, a reduction in both teacher agency and student empowerment; and in the other, an increase in teacher agency but an infringement upon student empowerment. Due to the limited space, I will provide only brief accounts of these two scenarios in the following section (but see Schulte, 2018a for more details).

Two Scenarios: Removing Agency and Side-Stepping the Curriculum

- ICT4E in Rural China: Scripted Lessons and Teacher Agency

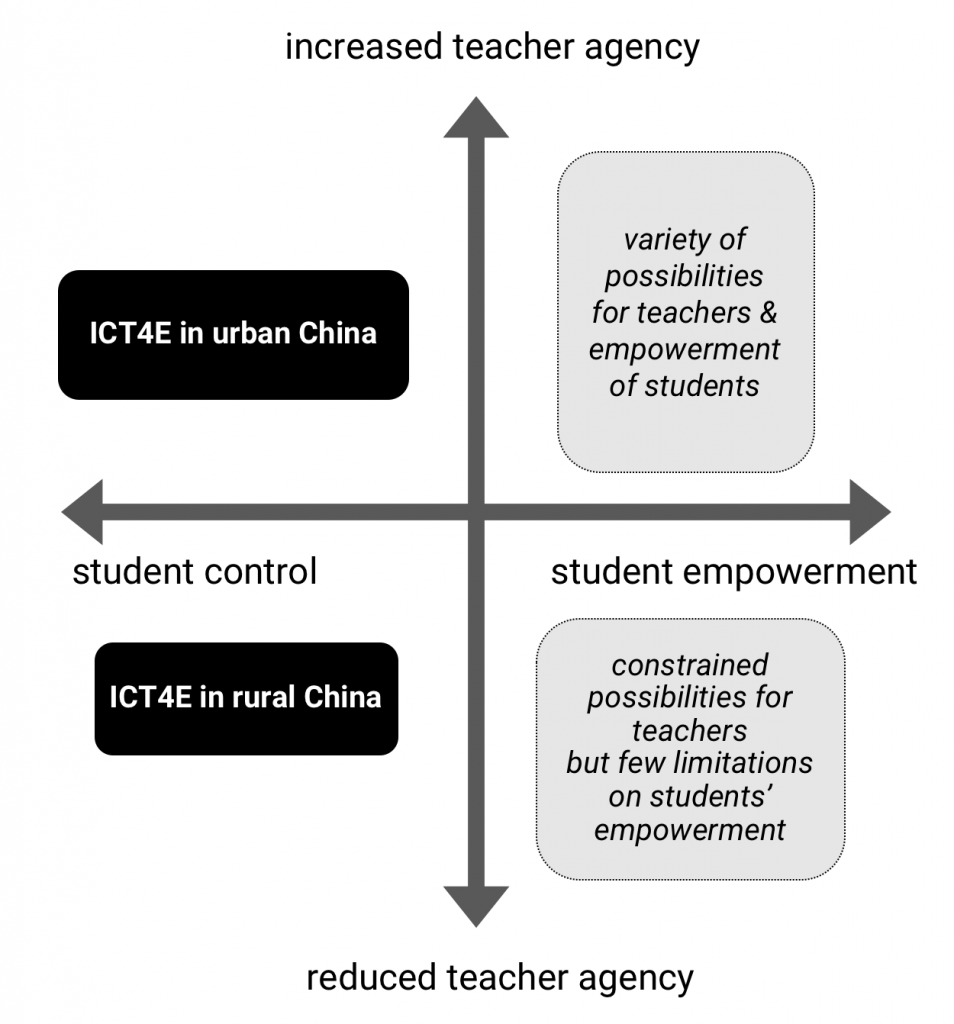

Potentially, ICT4E would have the possibility to increase both teacher agency and student empowerment in rural China (see upper right quadrant in Figure 1). This is due to several reasons, but primarily because, firstly, their adaptive nature would allow teaching and learning material to be more attuned to the school’s and students’ particular (social, cultural, ethnic, religious etc.) contexts and concerns; secondly, their responsive nature would allow teaching and learning to adopt a different pace for certain parts of the curriculum (e.g., those parts that can feel particularly remote to the rural student); and thirdly, their communicative nature would make it possible to integrate a feedback loop: potential difficulties experienced by rural teachers and learners could be mediated to the producers, which in turn could lead to an adaptation or re-modeling of the program, or even to a mode of co-producing it.

However, fieldwork findings suggest that the reverse is true (moving ICT4E in rural China to the bottom left quadrant in Figure 1). ICT4E were not adjusted to the specific local contexts, and not even to the larger region in which these contexts were located – some optional features on folklore aside. As teachers frequently

Figure 1. ICT4E in Relation to Teacher Agency and Student Empowerment

commented, both content and teaching strategies of the prescribed scripted lessons seemed alien to them, and often completely unusable with regard to their students. The programs were produced by elite schools in the regional centers (e.g., in the city of Chengdu for the province of Sichuan), and both the presentation of the material and the pace of how it should be taught made teachers repeatedly realize how much both they as teachers, and their schools and students in general, were lagging behind. They further felt that their specific expertise regarding local students was being devalued by imposing these decontextualized programs on them. Consequently, they either capitulated and reproduced, as expected of them, urban but alien teaching in their local contexts; or they resisted by modifying or eliminating parts of the program. In the latter case, students were given some space for self-development and cultural identification; in the former, they were being confronted with a culture that made their own environment look underdeveloped and inferior.

Ironically, ICT4E for rural China turned out to give even more credit to the already advantaged city schools: as these schools were used for producing the programs, they could earn additional credit and fame; while the blame for non-conformity or failure could be placed on the unprofessional rural teachers – thus removing rural teachers’ agency twice, and exacerbating the already existing divides. Needless to say, there is no bottom-up, or rural to urban, communication channel that could be used to influence and change, let alone co-produce, the programs.

- ICT4E in Urban China: Propaganda 2.0

Urban schools present a different picture, particularly in the advantaged urban areas. There is less perceived need to turn uncultured children into civilized subjects; instead, the urgent mission from the side of the Ministry of Education is to prepare Chinese students for the challenges of the twenty-first century knowledge economy (see Schulte, 2019). Again, potentially, ICT4E could help achieve such a mission goal, even though not by default of course. They can for example support students (and teachers) in turning to a variety of knowledge sources, break up subject-based divides, and share discussions across conventional boundaries (such as those of the nation).

However, classroom observations revealed two basic uses of ICT4E that defied such an orientation. Either they were used as one would use a printed book, that is, without any sort of interactivity or responsiveness, thus not altering the teaching and learning context in any substantial way. If there was any change at all, the modality of the lessons (use of micro-lectures, powerpoint presentations etc.) restricted students’ scopes of action even more. Or, and this was rather surprising, ICT4E were used to actually sidestep the curriculum – as preliminarily discussed with regard to the ‘politics of use’ above (thus moving ICT4E in urban China into the upper left quadrant in Figure 1): in particular, propaganda material was used that was not in line with the curriculum but rather a core concern of present government ideology. Thus, teachers used the leeway given to them in order to then exert agency on behalf of the government, while levering out the curriculum that stresses students’ autonomous thinking – a curriculum that had been developed and negotiated with much care and expertise since the late 1990s. When asked about their choices, teachers would stress the need to provide moral guidance to students in an environment that was marked by high-stakes examinations, and thus by the pursuit of individual gain, rather than by a concern for the collective. Explicitly referring to the Mao era and its stronger emphasis on moral issues, these teachers intended to re-moralize the classroom – drawing on central political ideologies (see my discussion in Schulte, 2018b).

Conclusion: Who Wins, Who Loses?

In the first example from rural China, the social structures impinging upon agency are further cemented, rather than dissolved. The producers of scripted lessons gain in value; while the reproducers lose twice: by being marked as underdeveloped, and by denying them acknowledgment of their locally specific professionalism. Different from urban teachers, rural teachers are not entrusted with agency, but are to act as unquestioning implementors – implementing however lessons that are far removed from these teachers’ (and their students’) realities.

As the urban example shows, teacher agency can be a two-edged sword. It may be used against the teachers’ immediate environment, either unconsciously, or deliberately in order to reintroduce e.g. political morals to the student collective, as was articulated by several teachers and principals; but at the same time, this perceived increase in local agency may in fact reinforce hegemonic discourses and power regimes. How well-equipped and willing are teachers – or for that matter, any kind of professionals – to question, dismantle, or even resist these regimes? Can increased local agency, combined with greater possibilities of communication and hence manipulation, open up a gateway for these regimes into communities and systems (such as the school system) that thereby lose, rather than gain, in autonomy? In a dystopian scenario (such as the one described above), teacher agency resembles a Trojan horse: it comes as a gift, but contains unpredictable dangers. Such dystopia is not limited to the merely political (or authoritarian) realm: it is equally conceivable that, for example, commercial interests are smuggled in along with the horse, or other ideologies that run counter to the core mission of the curriculum.

In both cases, there are clear losers. Firstly, students are denied self-determination and empowerment. In one case, they are turned into low-quality counterparts of their urban peers; in the other case, they are being cheated: under the banner of creative pedagogy, they are subjected to even more manipulation and control. Secondly, educational reformers and curriculum researchers who have been able to gain a voice in educational politics are being pushed out again through the back door: in the first case, it is the program producers in the regional centers who decide what kind of teachers rural China needs; often, they pursue their own agendas, including commercial interests when collaborating with the local ICT industry. In the second case, core concerns of educational reform are sidestepped in order to give more weight to central government ideology. What we can observe then is not just an increase, or a decrease, in teacher agency; but a struggle among groups of actors, in which a gain in agency for one group of actors may result in a loss in agency for another, while strengthening a third group, and so on. The peaceful notion of a mutual increase in agency, and thereby empowerment and democratization across groups, is a politically contingent scenario that may only be possible under very specific circumstances.

References

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy and its role in learning. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International Handbook of English Language Teaching (pp. 733–745). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46301-8_48

Cloonan, A., Hutchison, K., & Paatsch, L. (2019). Promoting teachers’ agency and creative teaching through research. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, online first. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-11-2018-0107

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Fontdevila, C., & Verger, A. (2015). The World Bank’s doublespeak on teachers: An analysis of ten years of lending and advice (p. 80). Retrieved from Education International website: http://download.eiie.org/Docs/WebDepot/World_Banks_Doublespeak_on_Teachers_Fontdevila_Verger_EI.pdf

Freire, P. (2005 [1970]). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). New York, NY: Continuum.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (Eds.). (2008). Digital literacies. Concepts, policies and practices (Vol. 30). New York, NY: Lang.

OECD. (2015). Students, computers and learning: Making the connection. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264239555-en

Pinto, L. E., Portelli, J. P., Rottmann, C., Pashby, K., Barrett, S. E., & Mujuwamariya, D. (2012). Social justice: The missing link in school administrators’ perspectives on teacher induction. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, (129). Retrieved from https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjeap/article/view/42826

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2013). Teachers as agents of change: teacher agency and emerging models of curriculum. In M. Priestley & G. Biesta (Eds.), Reinventing the curriculum: New trends in curriculum policy and practice (pp. 187-206). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Samoukovic, B. (2015). Re-conceptualizing teacher expertise: Teacher agency and expertise through a critical pedagogic framework (Doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa). https://doi.org/10.17077/etd.akfnhte1

Schulte, B. (2018a). Digital technologies for education in China: National ambitions meet local realities. In M. Stepan & J. Duckett (Eds.), Serve the people. Innovation and IT in China’s development agenda (pp. 31-38). Berlin: Mercator Institute for China Studies.

Schulte, B. (2018b). Envisioned and enacted practices: Educational policies and the ‘politics of use’ in schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(5), 624–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1502812

Schulte, B. (2019). Innovation and control: Universities, the knowledge economy and the authoritarian state in China. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 5(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2018.1535732

Wagner, D. A. (2018). Technology for education in low-income countries: Supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals. In I. A. Lubin (Ed.), ICT-supported innovations in small countries and developing regions. Perspectives and recommendations for international education (pp. 51-74). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67657-9_3

Wermke, W. (2013). Development and autonomy: Conceptualising teachers’ continuing professional development in different national contexts (Doctoral dissertation, Stockholm University). Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-86705

Wermke, W., Olason Rick, S., & Salokangas, M. (2019). Decision-making and control: Perceived autonomy of teachers in Germany and Sweden. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(3), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1482960

Recommended Citation

Acknowledgement

I am grateful for the generous funding from the Swedish Research Council (VR 2012-6530), the Crafoord Foundation (20160775), and the Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences (P11-0390:1).

Do you want to comment on this article? Please send your reply to editors@oneducation.net. Replies will be processed like invited contributions. This means they will be assessed according to standard criteria of quality, relevance, and civility. Please make sure to follow editorial policies and formatting guidelines.